Projet personnel

Le chemin des dames, the path of souls

A tribute to a couple of remarkable women in the great war 1914-1918: Lili Boulanger and Nelly Martyl.

A nurse runs.

A cellist plays a music

that no one can hear.

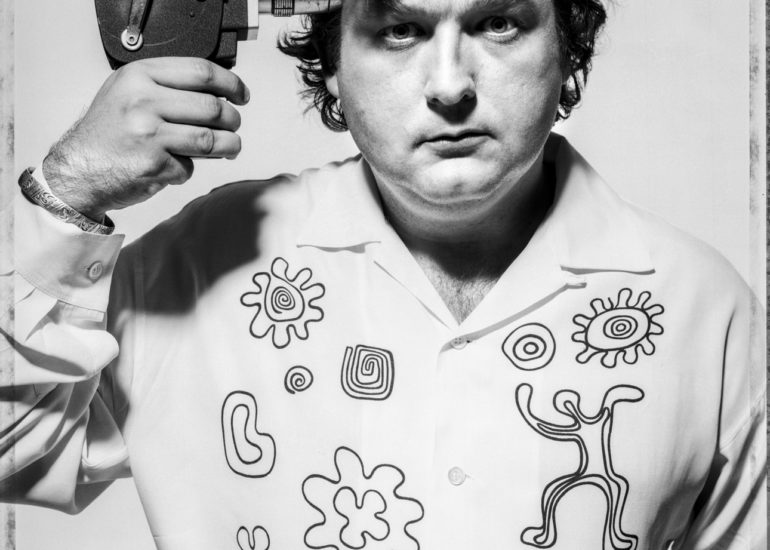

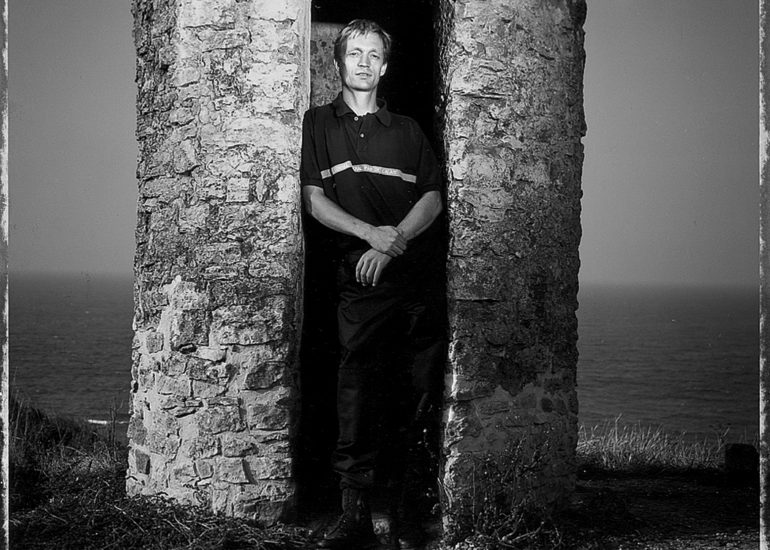

An unknown armed soldier

wanders in the loneliness

of a plowed land.

Two crossed destinies

Nurse-singer Nelly Martyl boosted the morale of the troops – a curious expression – by singing opera arias behind the battlefields. As to Lili Boulanger, who was she singing for in 1918, on her deathbed, when she whispered the last bars of her Pie Jesu as she no longer had the strength to go to her piano or even to hold a pencil?

Buried in the cemetery of Montmartre, Lili Boulanger has been resting in the silent world of the deceased for a century, alongside her sister Nadia. Back in 1953, just a few dozen meters from Lili’s grave, Nelly, the fairy of Verdun, had joined her, after a life devoted to helping the needy in her eponymous foundation, built in 1929 at 129 rue de Belleville in Paris. The building eventually succumbed to the wounds of time, the developers’ bulldozers having sadly erased its last traces in 2017.

While Lili Boulanger’s grave is still in bloom, Nelly’s burial site has been abandoned. However, scratching the foam lets her name reappear: Nelly Martyl née Martin, 1884-1953, widow of famed illustrator and painter Georges Scott. These women’s involvement in the Great War inspired my work. I set out on the scarred battlefields, with both a light and heavy heart, to meet these two ladies, these two souls

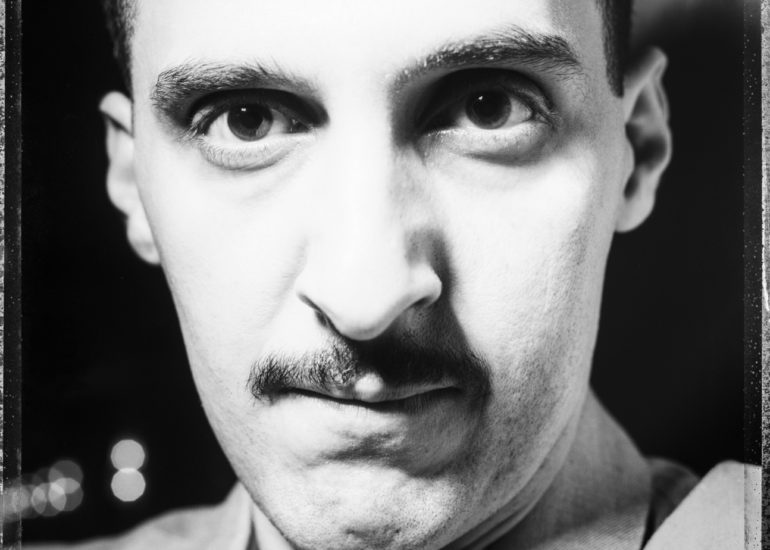

The nurse-singer

Some female stars of the period shared the patriotic craze by participating in the effort to entertain the soldiers within the framework of the Théâtre aux armées, founded by the painter Georges Scott.

Among these artists, opera singer Nelly Martyl, wife of Georges Scott. Far from the gilding and velvet of the Opéra-Comique, she began working as a volunteer nurse early on, at the Gare de l’Est hospital in Paris and in Artois, caring for injured « Poilus » returning from the front lines. In the summer of 1916, she joined the Verdun battlefield. Her courage and commitment commanded the admiration of the fighting troops. She gained the nickname of “The fairy of Verdun”. She was active on the Chemin des Dames in 1917 as well as in the Somme. Wounded and gassed, she was promoted to the rank of sergeant and decorated with the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur.

The composer

Away from the front, women like Lili Boulanger fulfilled a different destiny, in her case, that of a composer. A child in fragile health, she became in 1913 the first woman to win the Grand Prix de Rome for musical composition. In 1914, Lili Boulanger left for Italy to join the other laureates at the Villa Medici. It was there that she spent the first weeks of the war.

In December 1915, thanks to the support of the Franco-American Committee of the National Conservatory of Music and Declamation, she founded with Nadia, her younger sister and famous pedagogue, a gazette which enabled musicians away on the front to exchange news. Ten issues were published, until June 1918.

Suffering from intestinal tuberculosis, Lili Boulanger died exhausted on March 15,1918, at the age of twenty-four. Who, however, paid much attention to the death of a young woman as the apocalypse devastated Europe?

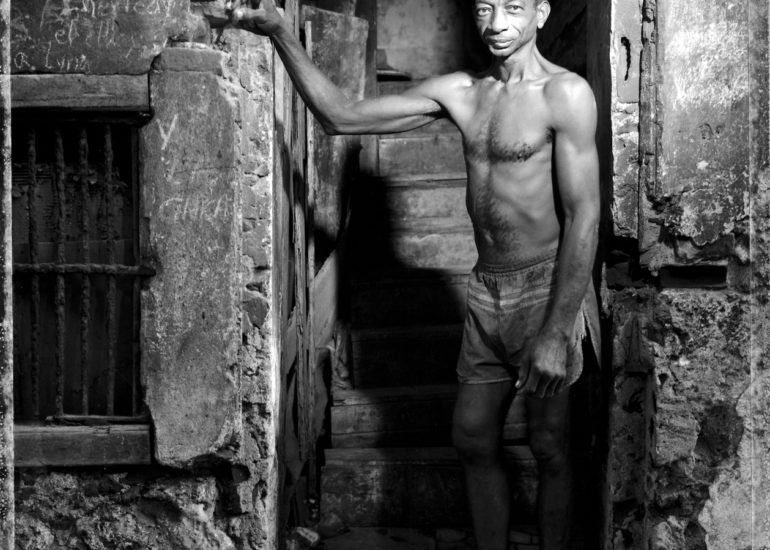

Le “Poilu“

August,1914. General mobilisation. It is widely acknowledged that the war will be short and victorious. Flowers to the gun, smiling and confident French soldiers leave for the front, escorted by crowds of women and children who applaud and embrace them. Older men knew best.

The heroes set off in midsummer for what was to be one of the most horrific carnages in history.

- One billion shells spent over 52 months.

- 6,000 deaths per day.

- Ten million casualties of all nationalities.

Empires and monarchies collapsing in an unprecedented bloodbath. In France alone, one out of two 20-year-old men died in the trenches. From the start of the hostilities, many women joined the ranks of volunteer nurses in field hospitals. Nicknamed “the white angels”, they nursed and comforted wounded and exhausted soldiers. They quickly became true icons of the First World War.

The howls of the earth

After the armistice, 120,000 hectares were declared a red zone in France because they were unfit for agriculture. The polluting presence in the soil of of heavy metals, toxic shells, bullets, human and animal corpses, made these lands dangerous.

The state therefore bought back these lands and handed them over to the Water and Forests Administration for reforestation. They planted conifers and then beeches. Nowadays, and particularly around Verdun, these places, once mutilated battlefields gutted by fierce fighting, are beautiful. Nature has reclaimed its rights there, slowly covering the gnawed concrete and the bristled scrap. Yet, the origin of the gentle curves of the landscape was none other than the shell and mine holes. Time could not totally erase the noise and fury of the past. It is enough to tread this land to feel the pain springing from the ground. Anyone who walks here, walks with the souls of the dead, and hears in the crisp whistling wind, the howls of those who have fallen and whose monuments, in all the towns and villages of France, recall their first and last names with a pathetic emphasis.